Translated by A. Hmangaihzuali Poonte

Long ago in a little village, there once lived a handsome young man named Raldawna. One day as he was clearing a plot of land with his mother, he saw the ruddy red fruit of a nightshade plant. Thinking it was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen, he said, “Mother, could there possibly be a girl as beautiful as this fruit?” His mother replied, “Yes, certainly, Tumchhingi lives just down that way.” Raldawna said, “Then let me go look for her,” and getting his mother’s permission, set out to look for Tumchhingi.

He came across a sturdy house and shot at its walls with his sling. The owner called out, “Who shot at our house?” “I, Raldawna,” he replied. But since Tumchhingi did not live there, he went on his way. Whenever he came across a house, he enquired if Tumchhingi lived there but she was in none of them.

Finally, at the end of the village, he came upon Tumchhingi’s home. She was sitting on a gong, weaving a puan, with a gun placed at her feet. “What are you looking for?” she asked. Raldawna explained how he had wanted to meet a girl as ruddy and beautiful as the nightshade fruit he had seen with his mother, and that he was looking for her, Tumchhingi. She replied, “If you want to marry me, you must talk to my parents.” So Raldawna met her parents and telling them the reason for his visit, asked for their permission to marry their daughter. They happily gave him their consent.

And so Raldawna and Tumchhingi were married. Taking all her possessions, Tumchhingi left her parents to follow her husband to his home. After they had traveled a long way, Tumchhingi said, “Raldawn, I thought I had taken all my belongings but I just remembered that I have forgotten my bronze comb.” He replied, “Alright, I’ll leave you on that bunyan tree and go back for your comb.” Lifting Tumchhingi to safety up on the branches of the tree, he then went back the way they had come.

Soon afterwards, a Phungpuinu¹ came trampling on cucumber peel right under the tree where Tumchhingi was hiding. Seeing Tumchhingi’s shadow on the ground, the Phungpuinu thought it was her’s and greatly admired herself. Muttering,

“Though my self carries nothing

My shadow wears bangles jingle jangle,

Necklaces jingle jangle,”

she stood under the tree, rocking herself back and forth. Tumchhingi watched from her perch high up in the tree. After a while she called out, “Phungpuinu, that is my shadow.” The Phungpuinu then looked up and saw Tumchhingi. “How did you climb up, Tumchhing?” she asked. Tumchhingi replied, “I climbed up on my back.” The Phungpuinu tried to climb the tree backwards but kept falling down with a heavy thump. “Tell me seriously, how did you climb up?” she asked again. “I climbed up sideways,” Tumchhingi replied. The Phungpuinu tried to climb up sideways but could not. Once again she asked Tumchhingi and this time, Tumchhingi told her the truth. The Phungpuinu then climbed right up to where Tumchhingi was sitting. “Let me wear your puan for a while,” she said to the girl and Tumchhingi gave it to her. Next she asked for Tumchhingi’s blouse, her necklaces and her bangles, and soon she was dressed in everything Tumchhingi had been wearing. Then she swallowed the terrified girl and turned herself into Tumchhingi.

After a long while, Raldawna returned. He thought Tumchhingi looked very different and said, “Tumchhing, how elongated your eyes have become.” She replied, “I kept telling myself there in the distance will Raldawna come, and straining my eyes watching for your return has made them elongated.” And so Raldawna took the Phungpuinu home. People had been waiting for his return, telling each other, “Raldawna is bringing home the beautiful Tumchhingi” and they swept the pathways and spread out their puan on the ground. But as soon as they saw the Phungpuinu, they exclaimed, ”Oh no, I will not let the Phungpuinu walk on my puan.” And they all hurriedly took away their puan, and so Raldawna took his new bride into his home.

Later the Phungpuinu went out to the outskirts of the village and vomited violently. Tumchhingi popped out and turned into a mango tree. She grew tall and strong and bore so much fruit that many people would come picking them. Eventually Raldawna too came to get some but only managed to get a small, misshapen mango. Saying, “This is not even good enough to eat,” he tucked it away on the bamboo-woven wall of his house.

Every day Raldawna and the Phungpuinu would go out to work in the fields. And whenever they were away, the little mango would jump down from the wall, turn into Tumchhingi and prepare the evening meal for them. After she had finished cooking, she would then turn back into a mango and tuck herself into the bamboo wall. Raldawna asked all his neighbours if they had seen anyone who had come into his house but nobody knew anything. So he finally decided to hide and see what happened while the Phungpuinu was out working in the fields.

When evening came, Tumchhingi jumped off the wall as usual. And as soon as he saw her, Raldawna caught her in his arms with great joy. Tumchhingi said, “No, let me go. I must turn back into a mango,” but he would not let her go. As they were struggling, the Phungpuinu came home from the fields. “Raldawn, let me in,” she called but Raldawna would not open the door.

The Phungpuinu then angrily broke down the door and came in. When she saw Tumchhingi, she became even angrier. So Raldawna prepared the two of them for a fight. He gave Tumchhingi a very sharp knife and the Phungpuinu a very blunt one. Tumchhingi easily killed the Phungpuinu, and she and Raldawna lived happily ever after.

¹a spirit, ghost, bogey, spook, ogress, goblin, hobgoblin (generally regarded as female)

Translated from the Serkawn Graded Reader - Mizo Thawnthu, Serkawn Centenary Edition, 2003, compiled and written by R. Nuchhungi (Pi Nuchhungi) and E.M. Chapman (Pi Zirtiri) in 1938.

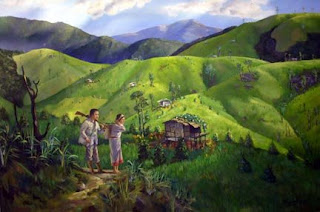

Picture:Autumn in Jhum, oil on canvas by Tlangrokhuma

Thank you for another good story, storyteller. An excellent translation. You are getting better n better with each translation.

ReplyDeleteThank you. Translating folktales is easy once you get a few details worked out. The language is invariably very simple and unadorned because these old stories are usually passed on orally and need nothing more than a straightforward rewriting in English.

ReplyDeletemizo thawnthu sap trong a lehlin ho hi a bu in la chhuah ula a tha ang..

ReplyDeletePretty good translation but it seems rushed in some parts. I would also suggest that you spend more time on bringing out the "feel" or work more on creating a connection between the reader and the story. This piece just seems too straightforward of a translation.

ReplyDeleteI never knew 'vani an rah' = nightshade! Listening to the story as a kid, I always thought 'vani an rah' was something exotic and fairy tale-ish :P Not something common, like nightshades. Oh well..

ReplyDeleteIt's such a good thing you guys are translating Mizo folk tales into English. I'd often thought of doing it, but managed only a few. Do think seriously about bringing out an anthology as suggested. Your translations, Cherie's, Margaret's, etc. could be put together.

ReplyDeleteI just printed out for my children. Looking forward to seeing other tales like Kawrdumbela, Mauruangi, etc.

ReplyDelete